Chris

McDonnell, UK

Chris

McDonnell, UKchristymac733@gmail.com

Chris

McDonnell, UK

Chris

McDonnell, UK

christymac733@gmail.com

Previous articles by Chris Comments welcome here

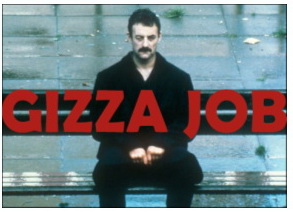

Give

us a job!

Change

can be stressful, rapid change even more so. When that stress is apparent

across social groupings, then its consequences can be serious.

This

month fifty years ago, May 68, saw upheaval on a massive scale in

So

where do we stand fifty years on? What have we learnt that can be of use

in managing where we find ourselves now?

In

the intervening years, here in the

According

to national statistics, unemployment is currently at a low level. Yet the

nature of the jobs that are available is cause for concern, with many

being taken on zero-hours contracts and the level of payment not

sufficient to manage a family. The growth of the need for food banks is

evidence of the underlying stress. Capitalism has its consequent

co-lateral damage. Recent reports identify an increase in the number of

children in poverty coming from low-income families requiring help.

As

the years go by our dependence on technology decreases the need for direct

hand skills, with production lines automated to such a degree that

production can be managed by fewer people. And we call it progress. For

sure, the process cannot be reversed so we have to find ways to manage

this changed society that are just and fair.

People

still identify themselves by name, where they live and what they do. It is

that personal pride that is crucially damaged by unemployment, it was that

loss that was poignantly, painfully, demonstrated by Yosser Hughes.

A

friend of mine who lectures in pastoral theology has a small note on the

Notice Board by her office door informing those who call that the ‘Carpenter

from Nazareth seeks joiners’, a job vacancy par excellence! In a

similar vein when she works with groups in parishes her response when

asked her trade is “I work for the

carpenter’s boy”, a succinct definition of a Christian vocation if

ever there was one. Being a Christian is an active role, a job that

demands effort, not just a label for form-filling. It was a significant

title that Dorothy Day gave her

Sometimes

communities of religious are criticised for avoiding the ‘real’ world.

That is to ignore the very core of their vocation, their being deeply

themselves. The American

Cistercian,

Thomas Merton described his vocation as that of

the marginalised.

There’s

a passage from Merton’s Asian Journal that indicates the monastic hope.

‘I

stand among you as one who offers a small message of hope, that first,

there are always people who dare to seek on the margin of society, who are

not dependent on social acceptance, not dependent on social routine, and

prefer a kind of free-floating existence under a state of risk. And among

these people, if they are faithful to their own calling, to their own

vocation, and to their own message from God, communication on the deepest

level is possible. And the deepest level of communication is not

communication, but communion. It is wordless. It is beyond words, and it

is beyond speech and beyond concept’.

The

work of the monk or nun, for it is indeed work demands, as it does for all

of us, good preparation, learning the necessary skills, acquiring

knowledge, patience and understanding suitable for the task. It involves

the transformation of our very being, rarely is it learned exclusively

through books. The apprentice pattern of the learner working alongside the

person of experience is indeed a worthwhile model. That is why our parish

communities should be nurseries, novitiates, of our Christian lives, not

merely replicas of drive-through coffee shops. We learn from being with

others, we gain from their experience.

We need to assist each other in our work for the carpenter’s boy.

END

=====